4/24/2015

We do not diagnose disease or recommend a dietary supplement for the treatment of disease. You should share this information with your physician who can determine what nutrition, disease and injury treatment regimen is best for you. You can search this site or the web for topics of interest that I may have written (use Dr Simone and topic).

“We provide truthful information without emotion or influence from the medical establishment, pharmaceutical industry, national organizations, special interest groups or government agencies.” Charles B Simone, M.MS., M.D.

PHYSICIAN BREAST EXAMINATION

Lawrenceville, NJ (Dr Simone) – This is an excerpt from my book, THE TRUTH ABOUT BREAST HEALTH-BREAST CANCER. http://www.princetoninstitute.com/#breast

Breast examination by a competent physician is important. Generally, physicians who spend the most amount of time doing the examination find the most lumps, and this was not linked to level of training or experience. In one study OB/GYN physicians found less lumps compared to internists, family practitioners, or any other physician who spent more time in doing the exam. It is difficult, however, to feel lumps that are less than 1 cm in size unless they are superficial. Since mammograms can miss 10 to 15 percent of all cancer lumps, some of which are quite large, physician’s examination is important to detect cancer.

Physician examination, not mammogram, was the main reason for the reduction of breast cancer mortality in the Health Insurance Plan Study which compared mammography to physical examination as a screening tool (used when a patient has no symptoms or obvious findings). In some studies, the physical examination is more accurate than a mammogram in indicating a breast mass that turns out to be cancer. Other studies show that the physician’s examination is equal to that of mammography for the detection of cancers.

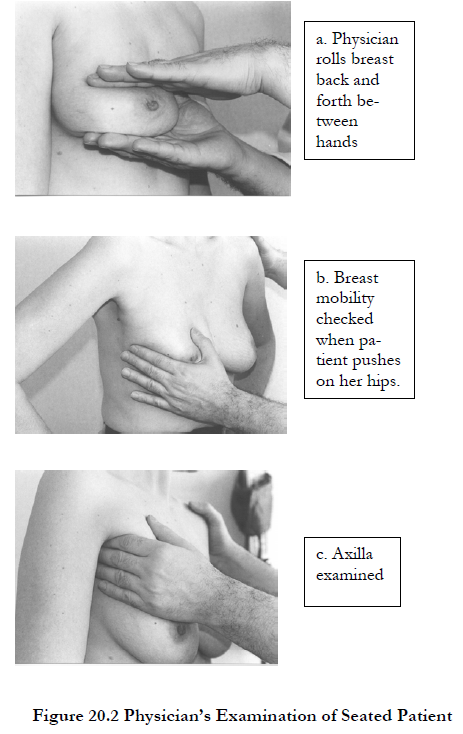

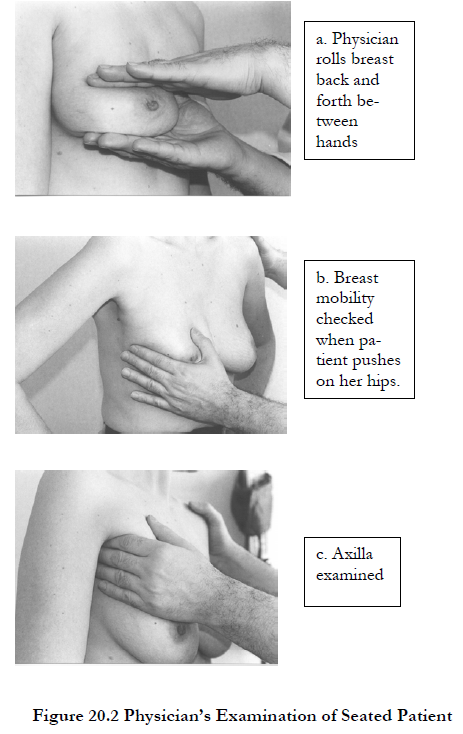

A good examination, as shown in 6 pictures on pages 174-176, can take from ten to fifteen minutes. These six pictures can save your life. The physician should first check for symmetry of the breasts, differences in size and shape, and ask the patient if any differences occurred recently. The breast surface should be inspected for dimpling or flattening, discoloration, ulceration, erosion, or dilated veins. Examination of the nipples should include determination of inversion, crusting or discharge, or deviation of one nipple compared to the other.

I first examine the patient seated on the examining table. With one hand underneath the breast, my other hand is pressing gently from the top of the breast and rolling the breast tissue back and forth to determine if there are any palpable masses in the breast between my two hands. The same type of examination can be done with hands on each side of the breast compressing together, again feeling for any masses that might be within the breast but between the two hands.

Next, the patient should put her hands on her hips and push down on her hips with force. If there is a malignant mass that is attached to the deep muscles, the mobility of the breast when the physician attempts to move it from side to side will be severely limited. For the next maneuver, the patient raises her arms above her head. The physician inspects the under portion of the breast, which is called the inframammary fold region. While in this position, the patient leans forward slightly so the physician can look for early nipple or skin retraction. Now, the patient puts her arms down along her sides in a relaxed position, and the physician examines the axilla. While doing this, the physician’s fingertips should roll underneath the pectoralis muscle to ensure the examination of the lymph nodes underneath that muscle high up in the axilla. Examination of the supraclavicular region, the region above the collar bone and near the neck, should be done.

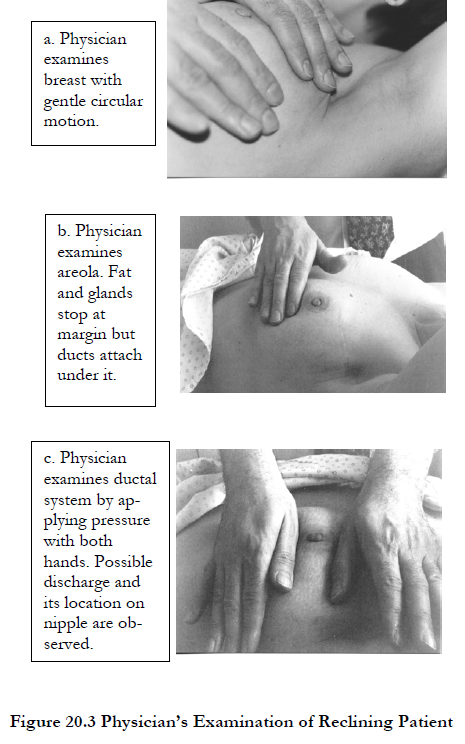

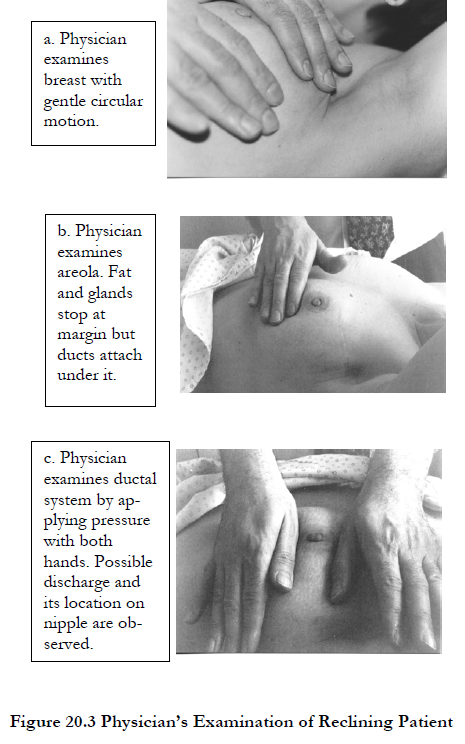

Now, the patient should be in a reclining position. The patient’s arms should be over her head and, if the breasts are large and pendulous, one hand of the physician should hold the breast on top of the chest wall while the examination is being performed. The method I find best is to plant my fingers on one area of the breast and, without lifting my fingers, examine that area for lumpiness or masses by pulling the breast in a circular motion with those fingers. Examination must be done gently; hard palpation can obliterate any sensation of small lumps beneath the examiner’s fingers. After this region of the breast is thoroughly examined, the physician’s hand should be lifted, put on another place on the breast, and the motion repeated until the entire breast is examined. If a lump is felt in the breast, it should be sequestered between two fingers and evaluated for hardness, buoyancy, and mobility. The inframammary fold area, the bottom most part of the breast, is sometimes difficult to examine because it normally is thickened and hardened in women who have larger breasts. Examination of this region must be thorough so that a small mass is not missed. Although breast cancers are infrequent in this region, time must be spent here.

Care and attention should also be given when the areola (the colored, circular area around the nipple) is examined since the consistency of the breast tissue is very different here. The fat and glandular material of the breast generally stops at the margin of the areola. Finally, the physician should examine the nipples for any discharge. To see if there is discharge, both hands should be used to form a concentric ring several centimeters away from the nipple and pressure should be applied. During the application of pressure, the physician’s hands should roll toward the nipple, thereby expressing any discharge from the ductal glands if, indeed, there is one.

(c) 2017 Charles B. Simone, M.MS., M.D.